Josh Reviews Dunkirk

In May of 1940, German forces had trapped the British Expeditionary Force, along with French and Belgian soldiers, along the northern French coast. The Allied troops pulled back to Dunkirk, but efforts at evacuation were at first thwarted by the German Luftwaffe. In what came to be known as the miracle of Dunkirk, the British navy, assisted by hundreds of small civilian merchant vessels, evacuated over 300,000 Allied soldiers from Dunkirk back to England. Christopher Nolan’s film, Dunkirk, follows three parallel stories: the soldiers trapped on the Dunkirk beach (the “mole”), a civilian sailor and two young boys who have set off to Dunkirk to assist the evacuation effort, and an RAF (Royal Air Force) Spitfire pilot in combat with the Luftwaffe.

Dunkirk is a powerful film, riveting in its depiction of this evacuation effort. Dunkirk is the story of a retreat, but it is as visceral and engaging a war film as ever I have seen, filled with depictions of the best and worst of humanity, of heroism and of cowardice in the fate of terror.

There is very little dialogue in Dunkirk. Mr. Nolan has crafted what I might call a tone poem of a film. The power of the story is conveyed by the performances, by the extraordinary visuals, by the crafty editing, and by the score.

It’s a cold film, one that often keeps its audience at a distance. This is the polar opposite of, say, Steven Spielberg’s approach in Saving Private Ryan. Mr. Spielberg and John Williams are experts at tugging on the heartstrings. Mr. Nolan (and his collaborator on the music Hans Zimmer — more on Mr. Zimmer’s work in a moment) take the exact opposite approach. They avoid any hint of sentimentality and schmaltz. There are many ways in which this could have failed. There are times when the nearly-silent Dunkirk reminds me of The Thin Red Line, a film which I love in places but which, ultimately, I feel does not succeed. But where that film stumbled, Mr. Nolan is able to pull together all of the elements of his film in a way that works beautifully, using an unusual approach to achieve a resonant thematic and emotional power.

Mr. Nolan and his frequent collaborator Hans Zimmer have, over the course of their films together, often gotten very experimental in their scores, frequently utilizing tones and sounds rather than traditional thematic elements. Dunkirk feels to me like the culmination of these efforts. This score uses an auditory illusion called a “Shepard tone” to develop an ever-increasing intensity. A “Shepard tone” gives the impression of an infinitely ascending tone, thus seeming to build and build and build without ever giving the audience a release. It’s quite a neat trick, and it works beautifully in the film.

Mr. Nolan has an incredible eye for constructing an image, and Dunkirk is packed with incredible, unforgettable images. There is a stark beauty throughout Dunkirk: on the beaches, on the sea, in the air. Mr. Nolan’s often wordless scenes use their visual beauty as a potent counterpoint to the human-caused carnage being witnessed during the battle. And the film’s depiction of WWII-era aerial combat are stunning.

Mr. Nolan is renowned for playing with the chronology and structure of his films (with Memento being the prime example), and Dunkirk features a neat trick of story-telling. As we watch the film and see its three main story-lines (the “mole,” the sea, and the air) intercut with one another, it seems that everything we are seeing is taking place at the same time. But as is made clear by the opening title cards (in a way that seems mysterious at first and then crystalizes as the film reaches its climax), these stories are not happening simultaneously. The events on the beach (the “mole”) take place over the course of a week, the events on the civilian boat take place over the course of a day, and the events in the air take place over the course of a single hour. When watching the film, as it became clear to me how the film was structured, I at first thought that perhaps Mr. Nolan was getting a little too clever for his own good. Isn’t this story powerful enough to be presented without this chronological trickery? And yet, by the end, I have to admit that I was impressed by Mr. Nolan’s choices. It’s extraordinary how he is able to progress all three stories in such a way that they build to connected climaxes in the film’s third act, despite their different time-frames. It’s a neat trick, and Mr. Nolan’s fiendish skill in pulling this off enables this to work in a way that it wouldn’t have in the hands of a lesser filmmaker.

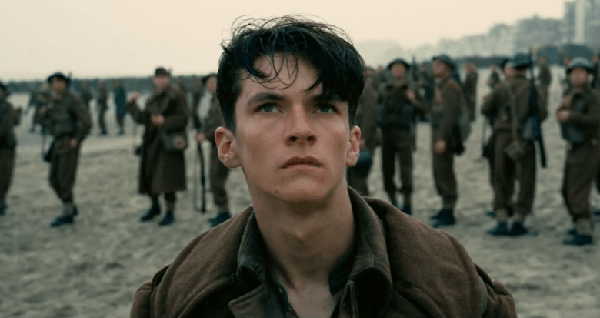

The cast is strong, though a weakness of the film is that we don’t really get to know any of the characters all that intimately. As is the case in many war films, all the young men wind up looking very similar to one another, such that I was sometimes confused as to which character was which. Fionn Whitehead plays the main young man who we follow in the sections of the film focusing on the soldiers attempting to find a way off of the Dunkirk beach, and he does strong work, showing us a lot of his emotion with his face and eyes, without being able to lean on a lot of dialogue.

The standout in the cast is, without question, Mark Rylance (Bridge of Spies) as the civilian sailor heading off to assist at Dunkirk. The character doesn’t really have a story-arc the way you’d expect in most traditional films, but Mr. Rylance is nevertheless gripping as he depicts a man heading wide-eyed into something he suspects will be terrible.

Christopher Nolan seems to love Tom Hardy’s eyes, as Mr. Nolan has once again cast Mr. Hardy in a main role and then put him in a mask that hides almost all of his face except his eyes. (Here, Mr. Hardy is a Spitfire pilot. Previously, he was the mask-wearing Bane in Mr. Nolan’s The Dark Knight Rises.) Mr. Hardy does strong work in a tough role, spending almost the entire movie in a cockpit, with little room to move, and his face mostly covered by his pilot breathing apparatus.

Other recognizable faces include Kenneth Branagh as the British commander overseeing the mole during the evacuation; James D’Arcy (Cloud Atlas) as a British Colonel also on the beach; and Cillian Murphy (another returning member of Mr. Nolan’s ensemble troupe, after having previously played Jonathan Crane in Batman Begins) as a shell-shocked soldier rescued by Mark Rylance’s character. (I also recognized the voice of frequent Christopher Nolan collaborator Michael Caine as the RAF man on the radio giving instructions to Tom Hardy’s pilot.)

I have to make note of Mr. Nolan’s choice to never once allow us to glimpse a German soldier. Even in the opening text screen at the start of the film, there is no mention made of “Germans” or “Nazis,” just “the enemy.” What an unusual choice! At the same time as Dunkirk is a recreation of a very specific time and place, it seems that Mr. Nolan is also looking to make broader statements about war and conflict, without limiting his film to being only about British men fighting Nazis.

Dunkirk is a very unusual war film; it’s a war film filtered through Christopher Nolan’s unique and very particular sensibilities. I love it for that, and for the film’s many unusual choices. I love how powerful it is despite the many ways in which the audience is kept at a distance from the film’s characters. I love how incredibly faithfully Mr. Nolan and his team of collaborators have brought to life these very specific events from this very specific time and place. Dunkirk is a great film, and one that I encourage you to see on as large a movie screen as possible.