Josh Reviews George Takei’s They Called Us Enemy

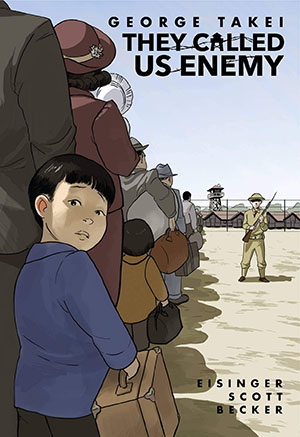

This graphic novel was written by Mr. Takei, along with Justin Eisinger and Steven Scott, and illustrated by Harmony Becker. The authors guide the reader through the story of Mr. Takei’s family. We see how his father, who was born in Japan and came to the United States as a teenager, and his mother, who was born in California and raised traditionlly Japanese, met and started a family. Simultaneously we read of the political dominoes that fell after Pearl Harbor, which led to FDR’s signing, seventy-four days after the attack, Executive Order 9066. This began the process in which people of Japanese ancestry were forced out of their homes, had their businesses and finances frozen, and were moved into camps.

As the graphic novel progresses, we follow Mr. Takei’s reminiscences as he charts his experiences growing up in a variety of these camps. His family was forced, at first, to live in the stables of the Santa Anita racetrack. (The causal inhumanity of this is staggering.) They were then moved by train, along with other Japanese Americans, to the Rohwer Internment Center in Arkansas. After several years there, the Takei family were moved into the higher-security Camp Tule Lake in Northern California, a maximum-security segregation camp for “disloyals”. In 1946, they were finally able to leave this camp, but rebuilding their lives was not easy, as the final portion of the book depicts.

This is a terrible, deeply moving story. It’s difficult to read at times. But I was impressed by how Mr. Takei and his co-writers were able to craft a story that could be accessible to younger readers as well as adults. Mr. Takei doesn’t pull any punches with his depiction of these atrocities. But neither did I think the book was too graphic to be appropriate for younger readers. (Framed by conversations both before reading and afterwards, my fourth-grade daughters both read this book last week and I think it was a powerful experience for them.)

I was impressed with how well Mr. Takei and his collaborators were able to pull the reader into the mindset and experiences he’d had as a little boy. Mr. Takei depicts, powerfully, how adaptable children are, and how they can make even the most unusual or unpleasant situations seem normal. And the book skillfully balances Mr. Takei’s personal childhood reminiscences with a concise history lesson that frames the context of the events that, as a boy, he of course wouldn’t have understood.

Harmony Becker’s beautiful black-and-white (and grayscale) artwork is a critical piece of how well the book works, and why this isn’t necessarily an adults-only read. Her energetic linework and cartoony stylization opens the door to readers of many different ages, while also helping ensure that this always feels — as it should — like the story of a little boy’s experiences. At the same time, there’s a deep craft and attention to detail on display in her artwork that spoke powerfully to a grizzled old long-time comic book reader like myself.

It’s painful to read this story not as a dusty history of mistakes made long ago and lessons learned, but as a morally outraged warning about the world we’re living in right now. The book quotes a number of U.S. politicians from the forties and hoists them on the petard of their own racist and inhuman words. And yet, just replace “Japanese” with “Mexican” or many other possible “others” and it felt to me at times like I was reading quotes ripped right out of today’s newspapers. (“They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists. And some, I assume, are good people.”)

As such, They Called Us Enemy is not just a wonderful graphic novel and memoir. I think it’s an essential text for right now.